6.1 Guiding principles for designing interventions

In supporting the media, SDC is aligned to international principles of media assistance (OECD 2014), and will apply the following five guiding principles

a. Adopt an holistic approach to media assistance Improving the media‘s capacity to play its multiple roles is best done if the media sector is considered as a whole. One should avoid merely limited interventions that support individual media outlets or even single journalists, or that promote information dissemination without attention to the infrastructure and environment needed to sustain free flow of information in the longer run. This implies working along a range of complementary entry points and pursuing a cross- and multi-media approach, based on the consumption habits of the population and longer-term trends in the development of digital media and their consumption (podcasts, video on demand, news platforms, etc.). SDC cannot address all challenges in the media sector in a given country; it needs to work in close collaboration and coordination with others.

This holistic approach implies a combination/coordination with other elements of democracy building ( UNDP and UNESCO 2019), which will be mutually beneficial. Media sustainability depends on economic potentials, an enabling legal environment, and political transparency. A combined approach to media and democratisation work is especially important in post-conflict societies, as independent media can hardly spring to life in non-democratic societies. Such a broad approach requires a sustained partnership with other supporters of democratic societies to create an enabling environment. Media indicators and audits should also be included in assessments of quality or effectiveness of governance in a given country, which is not the case at present. b. Action must be demand-driven at the local level, not supply-driven

SDC will focus on the rights, needs and means of local people and will try to conduct activities strictly oriented to these rights and needs. Supporting the media is not about fostering a specific technology or promoting certain communication channels for their own sake. The best form of media assistance is the development of domestic media in a country, based on the involvement of local women and men (tailor-made approach), encouraging links between media institutions and the rest of civil society. Cooperation with local civil society organisations (CSOs) and media actors will help determine media objectives and outcomes. Therefore, it is necessary to adapt SDC’s general vision of the role of the media for a democratic society to the local conditions and needs in each country. This should be done with and by local partners. Selecting capable local and regional partners should occur at the outset of a media project and is perhaps the most important step in the process of media development. This implies investing in a comprehensive assessment of the media sector, including a political economy evaluation of all actors, as well as baseline studies to measure and understand local consumption habits and needs. The target audience and the purpose of the media intervention will define which types of media to work with and support, including public media, community-based media or private media. These partners should take the lead; the role of the international community is to help enlarge the space in which those media outlets operate.

c. Think long term The media sector is complex and comprises many different actors. Therefore, supporting a well-functioning media sector with the necessary institutional infrastructure needs time and long-term strategic programming. This requires dedicated commitment in what is basically a prolonged process of institutionalising democracy.

Particular attention should be devoted to supporting independent, sustainable and capable local media. It is important to address financial sustainability, with media business plans linked to economic prospects. In a post-conflict situation or an emerging democracy, media should be gradually weaned from any dependence on donors as

national civic and economic mechanisms develop. However, this transition could require a decade or more. Training in managerial skills and revenue generation capacities takes time, and there needs to be progress in building an enabling environment alongside developing the capacities of the local media.

d. Place emphasis on (donor) coordination

Coordination of media assistance among the various actors involved includes not only donors, but also national authorities, regional and multilateral agents, and private actors from the media sector itself.

In most partner countries, the media sector is very small, which means there are few partner organisations to work with. As a result, donor organisations often turn to the same partners time and again. In addition, given the short history of media assistance, many actors have only recently begun to formalise their missions and develop strategies. All of this increases the need for close cooperation with other actors and particularly with donors. This can include sharing of audience surveys, coordination for impact assessment, creation of media development coordination groups and meetings, creation of media basket funds, sharing best practices, forming coalitions, addressing common regional or thematic media development issues, etc. This is especially necessary if donors want to implement the comprehensive approach mentioned earlier. An initiative exploring the feasibility of establishing an ‘International Fund for Public Interest Media’ to attract and deploy new capital to the sector. It stems from the observation that in order to strengthen independent media and to protect press freedom around the world, there is an urgent need for a radical increase in support and funding for public interest media. This initiative received the support of Luminate, which was founded by and is funded by the The Omidyar Group, and was conducted in collaboration with BBC Media Action and others through an extensive consultation process with media and media support organisations around the world, donors, technology companies and other interested parties.

|

e. Support systematic research on the effects of media and access to information on democratic governanceIn addition to monitoring and evaluation (M&E), research should be part of any media support project, but should also be supported in its own right to advance understanding of the role of the media in governance in different political, economic and social contexts. This includes testing our assumptions about the influence of the media on political participation, public debate, policy and accountability dynamics. Yet one needs to be realistic about what can and cannot be attributed to the media, as evidence is hard to obtain. (See

section 9 for more on M&E and the impact of media programmes.)

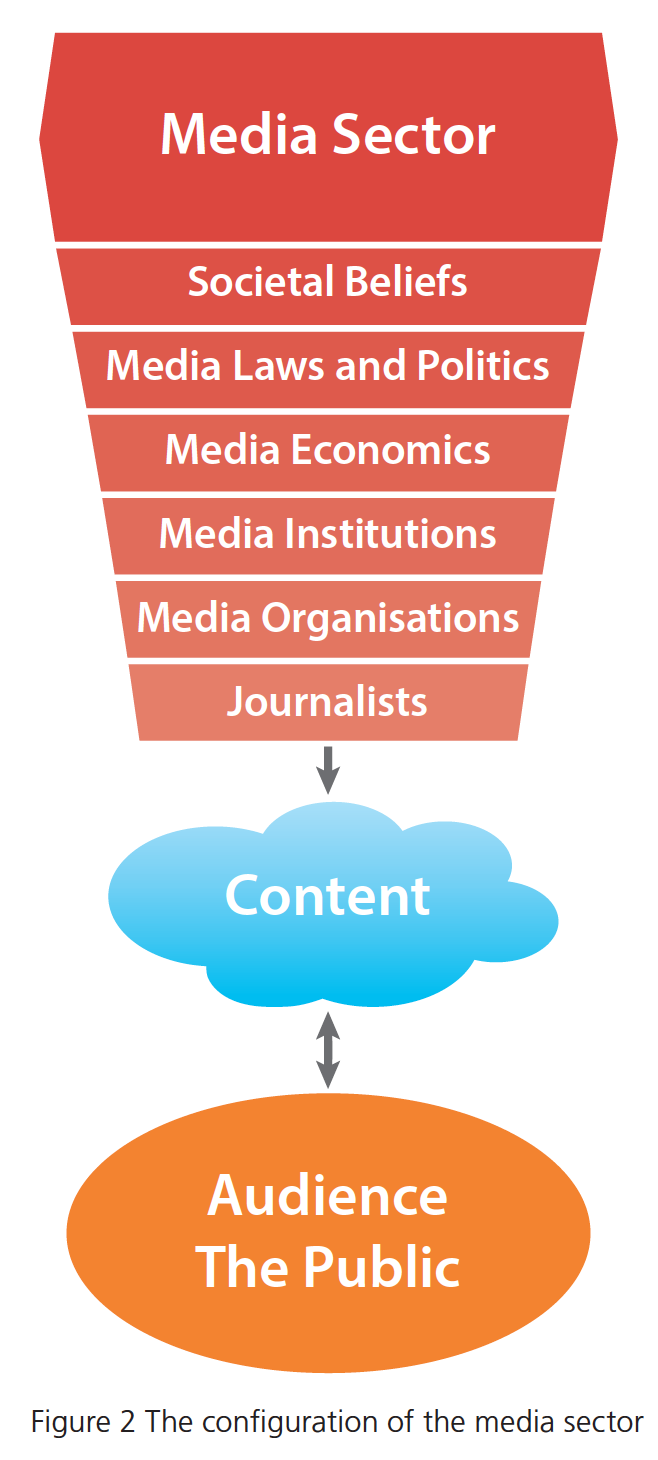

The SDC approach to media assistance is oriented towards the six different segments of the media sector, which are all interconnected and influence each other (see Figure 2,

click to enlarge). Each segment is a potential entry point, and media assistance is most effective when it addresses several segments in combination.

|

|

Table 1 Overview of the six media sector segments and possible interventions

Segment of the media sector

|

Possible interventions

| Individual journalists

| Training on ethics and technical journalism skills

Training on thematic issues

| Media outlets

| Training for different types of media: public service broadcasters, community radios, private TV or newspapers

Capacity building on management, technical maintenance, income generation, etc.

| Media institutions

| Support to journalism schools

Support to media regulation and self-regulation actors

| Economic and technological factors

| Training on business plan and business management

Improve overall economic factors for the media sector

Training on new technologies and related opportunities

| Political and legal environment, and safety

| Support political will for an enabling media environment

Support legal reforms

Training on safety and security of journalists and media outlets

| Societal beliefs and cultural values

| Support societal vision of media as the fourth estate

Training on media and information literacy programmes in schools and for adults

|

Any intervention should start with a proper analysis of the media environment and all six segments as well as the social, economic, cultural and political factors that shape the media environment, and the needs, risks and potentials. The choice of the types of intervention depends on the findings of the analysis and programmes already conducted by other donors or media actors. (For a checklist of the media segments’ analysis, please refer to

Annexe 2.)

Ultimately, what matters is what people get to read, listen to and view via the media. However, it is important to remember that citizens (audiences at large) are not only the target group but also actors or influencers in the media environment. Their role should be taken into consideration in each segment.

The following section describes in more detail each of the six media segments, providing a short introduction, potential interventions, and issues to keep in mind.

Journalists are the main entry point of media assistance efforts as they are key in the production of media outputs. Their level of performance is contingent upon their individual knowledge, capacity and personality, on the role models they have adopted, and the resources (finances, time) they are given. They have a certain scope of action that is extendable, but restricted by other spheres of influence.

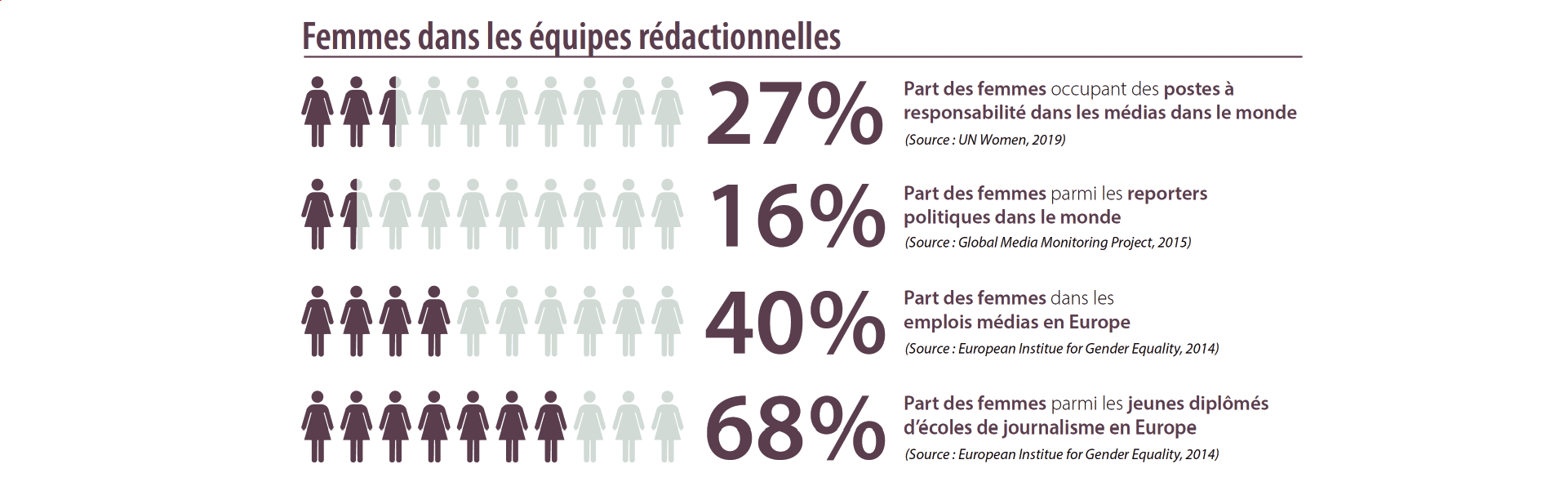

Generally, journalists should have competencies in media ethics, professional skills, knowledge of the subject they cover, and awareness of particular elements in their personal beliefs. In many cases, the level of professional journalistic skills is very low, among novices and working journalists alike. For example, the wide array of different journalism concepts and role models stressing different foci in professional journalism is hardly known to many journalists. Newsroom and media teams remain male-dominated. Though there are new human resources policies and incentives to hire and promote women as journalists and editors, when working with this sector it is important to be aware of the lack of representation of women, and to include them in various approaches to media assistance.

Potential interventions: training of journalists Potential subjects for training should be based on the needs revealed in the analysis, but are likely to include the following.

Raising the level of skills in professional journalism (writing, editing, acquaintance with different formats like news, reports, comments). Establishing professional standards and ethics in journalism. Specialised knowledge like business and finance, conflict dynamics, politics, environment, HIV/ AIDS or sensitivity to human rights. (Thematic training should be offered only when the basics and fundamentals of journalism have been mastered.) Knowledge of legal rights and duties. Editorial management. Gender (gender-sensitive language, use of non-stereotypical images of women and men in the media). Training in multi-media production, with content that is people-driven rather than technology-driven. Training in knowing how to better target specific audiences such as youth, or urban or rural populations. Training on data and use of ICTs, including data collection, verification and analysis, data visualisation and storytelling, as well as engaging with users and managing interactions with communities. Training on safety and security, including psycho-socio trauma protection.

Types of training

These issues can be covered by different types of training: workshops, seminars, long-term courses and study programmes, internships, training of trainers and in-situ training, conducted by different profiles of trainers (international, local or third country experts) and in different locations (in or out of the country).

On-the-job training does not require the same approach and skills as training delivered in schools or academic settings. The curriculum for on-the-job training programmes needs to consider the constraints facing participants – mainly the fact that they still have to produce content and deliver their services while being trained.

A large amount of training is provided for individual journalists, convening them in a special location outside their working environment, and covering specific issues. The benefits of this are as follows.

It can be easily conducted, has low organisational costs (room, trainer, participants) and can be quickly implemented.It can be tailored to the needs of participants ineach and every single case.The size of the group is usually small (8–12people), which provides a good learning atmosphere that is conducive to learning new skills and capacities.Multiplier effects seem easy to achieve when trained journalists work for different media, sharing new skills with colleagues.

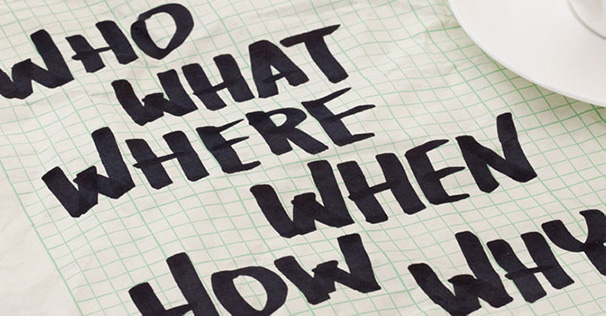

Always answering the 5 Ws (What? Who? Where? When? Why?) is the cardinal rule of journalism. There can be no compromising when it comes to the first four Ws. The audience needs landmarks : Where did it happen? When? Who's involved? What happened?

|

|

Issues to keep in mind

The best training for journalists is training that gives them the chance to put their learning into practice. On-site training (where the journalists work) also allows for direct adaptation of and changes to the production chain. Any training programme should be developed based on discussions with potential trainees and their supervisors, to ensure a tailor-made intervention design. Individual training seems mostly appropriate for learning on specific themes that journalists write about and report on (e.g. acquiring knowledge in business, finance, environment, etc.). Yet the overall structure of the media needs to be considered, and in-depth discussions with editors need to take place prior to deciding to train a journalist in a specialist field such as finance or health. Few media have the luxury of employing specialist journalists within their newsroom teams and will, in the long term, optimise the training. New actors such as bloggers and communication officers are also often wrongly associated with the work of journalists. Like any citizens that have the opportunity to write and share content on digital media or to create platforms, bloggers and communication officers are not usually journalists.They have not been trained in journalism ethics and do not work for a media organisation based on an editorial line/charter and are not subject to supervision by an editor-in-chief. Like medical doctors and lawyers, journalists are professionals whose skills are validated by a degree or professional media body. The outcomes and impacts of individual training are difficult to monitor. It is, however, important to test journalist training approaches by monitoring whether trained journalists apply the new skills in their professional life, and if not, what prevents them doing so. Sustainability is often questioned, as few if any studies have followed the work of trained journalists over a long period (10–15 years).

Media production depends not only on trained journalists but also on media outlets providing the required infrastructure, financial resources and working conditions that allow for professional and independent journalism. Training for reporters might have hardly any impact if they are hindered by their editors or employers in implementing what they have learned. The way single media outlets are institutionally organised largely determines how internal power is distributed, along with which journalism concepts and role models are established. The revenue structure also influences the media’s performance. Those with high circulation and considerable income from subscriptions might be more independent editorially than those with high reliance on advertisements. In many developing countries, media are community based or not for profit, and rely mainly on international donors’ support. Their business model is thus more hybrid and not based on traditional media business models. Potential interventions: training at organisational level

Training makes more sense when editors, sub-editors, editors-in-chief and managers (rather than just journalists and reporters) are also involved. This might include:

an in-situ, one-week training programme for community media (radios)exchange programmes between media, within one country or between media from the same sub-region, or ‘South–South’on-site training in ethics and journalism conceptsfor editorial teams, including editors-in-chief/ownersroundtables for ethical issues with media leaders/owners (ensuring that women are represented);establishment of adapted professional standards and editorial guidelinestraining on multi-media production, social media positioning and community managementtraining on managerial skills and internal governance for middle management, executive and governance bodytraining on income generation, including the partnerships for institutional communication campaigns.

Support to single media organisations

Although some caution is needed to avoid getting too close to one partner and/or creating a monopoly, in some specific contexts, only one or two media may be meeting the minimum requirements to receive SDC support. In these cases, supporting single media outlets might be relevant if particular efforts are invested in fostering internal pluralism and inclusiveness in the editorial team’s composition and content production (i.e. ensuring appropriate representation of women, people of different ethnic origin and marginalised groups).

Contingent upon the analysis conducted, it might be appropriate to support single media outlets in various ways, as follows. Support the creation of a new national media (where the situation is one of a media ‘desert’ or totally co-opted media landscape).Embark on a programme to reform state media into a public service broadcaster (only if there is the political will nationally to do so).Support a UN media set-up as part of a peacekeeping mission in a conflict zone or its transition to local ownership at the end of the UN mandate.Middle way option: a production studio that broadcasts media content through a network of local media partners.Provision of material or financial assistance for infrastructure needed to ensure media independence; assistance for technical capacity (computers, software, transmitters, cameras, printing presses, paying for photo services or news wire subscriptions), and providing access to capital and loans.Provision of ICT for editorial offices to strengthen their capacity to gather and analyse data andinformation.Provision of training for the whole staff of the media (not only editorial, but also support staff, management and marketing services).

|

|

Issues to keep in mind

The organisational difference between public broadcasting, community-based media and private media might require differentiated approaches. For example, a special case of supporting single media is transforming former state broadcasters into public service broadcasters (PSBs). This could have considerable impact as PSBs reach a large audience. But there are also political risks, as governments usually lack the political will to cede control of the airwaves to the public sector. As politics still dominate the media, any political change during this transformation might jeopardise the success ofthe project – e.g. by changing legal conditions or by pressurising the broadcasters‘ staff.

On-site training allows for training of staff othe rthan journalists, either in the editorial rooms, or even in support departments (technical, human resources, management, finance, marketing, etc.).This is, in some cases, an alternative to individual training. Training takes place in the workplace and comprises people from all levels of the hierarchy,which can deliver real change in a single media as all levels of the hierarchy are included and (hopefully) convinced to put what they learn into practice. Thus, a positive outcome is much more likely than from individual training. This kind of training is best for learning new reporting styles, ethical guidelines, different journalism concepts, particularly when all decision-makers in editorial and management are involved. Nevertheless, this kind of training is more expensive (as it involves more participants). Follow-up is more difficult, as it eats up time for all staff. Donors and managers should keep in mind that the training is useless if there is rapid staff turnover, thus for some key positions, the rule of ‘2 people for 1 position’ should be strictly applied.

There are pros and cons in supporting single high-performance local media. Besides being an asset in themselves, they can also serve as a model that sets standards and influences other media tofollow their quality guidelines and performance. Good-quality production and recognition might also lead to improved revenues and independence.On the other hand, the multiplier effects beyond this single media are more difficult to achieve (unless the media outlet belongs to or becomes a leading media in the country/ice-breaker effect). This holds the risk of failure as it focuses on very few partners. Usually, a great deal of money is involved (infrastructure plus staff, etc.), which might then be lacking in other places; strong links between one donor and a media outlet also bearthe risk of the donor being held responsible for content. But overall, it seems an option that is worthwhile to consider. As audio-visual media play a major role for the public, it is worth the effort to contribute to the establishment of a leading media that realises the quality required in terms of impartiality, balance, diversity and transparency, from which other media organisations can learn.

Media outlets need to be surrounded by a professional sector composed of media institutions supporting the whole sector with services a single media outlet cannot afford alone. These institutions include education, training and research institutions (universities, institutes); press councils; journalists’ unions; press clubs; and watchdog organisations. This institutional structure needs to be sufficiently set up, independent, and up to the task. It is particularly appropriate to work with them when a donor attaches special importance to serving the whole sector without getting close to only one partner. A thorough analysis, however, is needed to determine which kind of institution is necessary and which ones are independent and reliable.

ARTICLE 19: In today’s world, dominant tech companies hold considerable power over what users can say, read and watch online. Social media companies’ content moderation practices have a huge impact on public debate, but they are often opaque and unaccountable. Increasingly, these content moderation practices are impacting users’ human rights, including the right to freedom of expression.

This is why we’re calling for the creation of the Social Media Council. A new transparent, inclusive, independent and accountable mechanism to address content moderation problems using international human rights laws as the basis.

We want to make sure that decisions on content moderation are compatible with the requirements of international human rights standards and are shaped by a diverse range of expertise and perspectives.

|

|

Potential interventions: support to training institutionsIn the field of capacity building, some projects choose to institutionalise training by supporting training institutions that serve the whole sector. These include journalism schools, media and communication departments of universities, media houses, etc. This offers some obvious advantages:

Sharing a common training institute between different media might be an economic alternative to funding training by individual media, or completely by participant fees.This training approach is appropriate when a substantial training need has been identified for the whole sector and exchange opportunities among media people need to be created.This approach supports the whole media sector.Some of these institutions can be very flexible in training content, schemes and formats to adapt to the changing media environment.Networking among journalists takes place almost automatically in such an institution.It can also serve as a neutral platform to discuss issues affecting the media community.The local media community can develop ownership more easily than with individual courses or on-site training.

Still, sustainability of these training institutions is very difficult to achieve. It requires hybrid financial solutions such as public support, private investments and, at a minimum, a favourable media environment for media owners to invest in journalist training or contribute to the costs.

It is very difficult to assess the performance of these different approaches regarding efficiency and effectiveness. This is due to the low level of M&E still encountered in most media assistance work. Serious evaluation needs to be developed in future projects, particularly looking at how trained journalists and graduates from these media training institutions become integrated into the job market.

Type of actors per function

|

Possible interventions

| Capacity buildingJournalism schools, university departments (mass communication and journalism), adult training centres, etc.

| Introduction of new curricula (ethics, multi-media, new technologies, etc.)

Introduction of practical training (in-house production studio, university media, etc.)

Institutional training (strategic management, business plan training)

| Auto-regulation / independent / self-regulatory institutionsMedia councils, press councils, media houses, media watchdog and monitoring groups, media and communication high authorities, ombudsmen, press complaints commissions, etc.

| Development of clear mission and strategies

Training of management and staff (strategic management, business plan training)

Introduction of media monitoring capacity

Development of codes, guidelines, support to the sector

| Protection and defence of the sectorTrade unions, associations of journalists, associations for the safety of journalists and media actors, editors’ guilds, broadcasting associations, etc.

| Institutional management training, advocacy training, business plan training, coalitions training, communication and national/regional and international networking

| Measure, study and research for the sectorMedia audience measures, research institutes, media monitoring institutions, advertising associations

| Workshops to define research questions and needs, creation of joint interest groups (‘médiamétrie’, the audience measure institute, the media and the advertisers), training of management and staff (strategic management, business plan training)

|

Issues to keep in mind

Supporting self-regulatory institutions, professional associations, media monitoring groups and press clubs has become a widespread activity in media assistance. Establishing this kind of institution means supporting the whole media sector and strengthening local media institutions in their interplay with government and other actors.

These institutions are for the benefit of all media actors and, more broadly, governance and democracy actors. This type of support may provide a good return on investments when calculating the ratio costs/beneficiaries, as these training institutions provide strong leverage for improving the capacities of the media sector as a whole. However, some of these institutions may not be totally independent from political pressures and may not be able to fulfil their mandates. Their sustainability is difficult to achieve when the media sector is still economically weak. Furthermore, the long-term outcomes and impacts of these institutions are difficult to assess.

It is self-evident that the overall economic and technology conditions of a country are an important factor for the country’s media. Purchasing power of ordinary people will have an influence on newspaper and media’s subscriptions and circulation, which in turn will influence the media’s ability to pay their staff decent wages and thus limit corruption and other negative incentives. Economic conditions largely determine the potential revenue media can expect to raise from advertisements and subscriptions. Besides this, the diversity of media ownership and the degree of media concentration are critical features of a healthy media environment.

In contemporary digital media landscapes, the control of the narratives is increasingly in the hands of a few international private actors (such as the GAFAM and the way they design their algorithms). At the same time, the architecture of the infrastructure of information flows at the national level remains very much in the hands of states that have the capacity to control or cut off internet access in the whole country.

Regarding media content production and broadcasting, recent technology evolutions have drastically cut equipment costs. The digitalisation of production allows journalists to work with relatively cheap recorders or just mobile phones. Internet and mobile communication technologies have expanded the potential reach of media content as never before.

Ultimately, what is most important, and most costly in terms of a media budget, is to have trained and technology-agile staff who are fairly and regularly paid by the media owner. However, the traditional business models of media are jeopardised by the capture of advertising revenues by internet platforms such as the GAFAM and the ‘click economy’. This is why, given the general crisis in media finances, the role and potential of public funding to support the media should be discussed more widely and integrated into donors’ overall strategies.

Potential interventions

Improve the financial sustainability of the media so that they can pay their staff and be responsible employers (e.g. supporting a minimum wage for journalists, existence of means of productions, etc.) by promoting hybrid financing: revenue generation by commercial advertising and institutional communication campaigns, crowdfunding, facilitating access to different private sector and public funds, support from donors or foundations.Develop fundraising capacities within not-for-profit media (private foundations grant-writing, donors procedures, etc.).Strengthen general market conditions for media, facilitating yearly market benchmarking for advertising (for instance) or the support for the creation of media coalitions to face the weight and the pressure of advertisers (weakly structured advertising market, notably in fragile contexts).Favour anti-monopolistic activities by improving access to and ownership of the means of production, printing and distribution.Support better transparency of media ownership.Finance general infrastructure for better technical outreach, and improve distribution channels outside urban areas to reach a wider audience (without creating market distortions).Raise the level of training in business management skills in media (participants: managers, owners; training content: business management, marketing, advertising, ethical guidelines).

Issues to keep in mind

Economic and technological interventions normally serve the whole media sector. In some cases, they are of high importance as they form the basic conditions for any media development. Donors should be ready to face the vast challenges linked to internet and mobile services on the media economy (including the capture of advertising revenues by internet platforms and the ‘click economy’), and should shoulder the political risks associated with such a programme (e.g. question backdoors agreement between repressive states and internet/phone providers, digital surveillance capacity, condemn illegitimate cutting off of internet access, etc.).

The general economic and technological environment of a country is normally beyond the scope of a single media assistance intervention. However, there are activities in the economic sector as well as in the technology sector that directly determine the media’s performance, such as anti-monopolistic efforts, media management training, or supporting infrastructure for better technical outreach (fibre-cable, satellite coverage, new transmitters, etc.). Even simple measures in this sector can have large positive impacts, and each effort to strengthen the media’s economic viability in the long run decreases dependency on donor funding.

Yet some economic or technological measures may be inclined to produce market distortions. Thorough analysis and planning are needed to avoid such counterproductive effects. There are hardly any ‘purely economic’ activities; thus, some people become empowered, others disempowered. Donors and implementers should be aware of these political side-effects.

The media sector is a reflection of its wider environment and particularly of its political environment. This is why a political and power analysis is so useful to understand the media sector and how the distribution of communication power is allocated within a society. Although the political sphere is outside the media sector, each influences the other. The media sector influences the political sphere, because it: (a) influences the audience (i.e. citizens/voters), which in turn may put pressure on governments; and (b) enables discussion within the political sphere – for example, between political parties.

An enabling legal environment is an essential pillar for free and independent media. It ensures respect for the rule of law, media-specific laws, and institutional structures supporting free and independent media (CIMA 2007: 4). The political and legal environment are distinct but connected, as political actors influence the formulation, implementation or avoidance of laws.

However, attention should not only focus on (high-level) political actors but also more widely on the various officials of the judicial and bureaucratic apparatus that interpret the rules and decide how they should be applied (UNESCO 2018).

Media-specific laws include regulations on information gathering, such as a freedom of information act or access to information act that mandate the national government and other actors to disclose certain data to the general public upon request. They also include content-based regulation and subsequent punishment for perceived abuses such as libel and slander. This regulation will influence the risks of self-censorship in journalism. Media-specific laws also include regulatory measures such as (for instance) licensing for broadcasting, the provision of air frequencies, and the recognition of the profession of journalists (delivery of press cards).

|

|

By restructuring the media market or manipulating the distribution of resources in the market, media regulatory interventions can increase or decrease the likelihood of certain viewpoints reaching audiences. These interventions can fall into the category of ‘soft censorship’ or indirect censorship. They increase the political and economic vulnerability of individual players in the media system, and the likelihood of editorial compromises in the interest of securing available resources (Polyák and Meuter 2016). The increasing role of new actors on digital platforms, from the GAFAM to individual bloggers, comes largely into a legal vacuum in emerging and developing countries.

Potential interventions

Training of CSOs, journalists, lawyers, judges and regulatory bodies and law students on the legal frameworks and remedies for ensuring freedom of the media. Support local capacity to advocate for legal reform and promotion of a media freedom agenda. Provide support to litigation of media freedom cases at the national and international levels. Deploy international observers attending trials of media actors. Provide media and information literacy programmes for parliamentarians, elected executive, decision-makers, traditional or religious leaders, etc. Provide specific training for members of parliaments (MPs) on the role of media and ways to build constructive relationships with media organisations. Organise joint workshops between political parties, media and journalists to foster understanding, respect and trust.

Issues to keep in mind

Regional bodies, such as the Council of Europe, the African Union (AU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), have texts and conventions that can serve to improve national legal frameworks. The existence and quality of legislation on freedom of expression, mass media, public broadcasting, regulatory bodies, licenses, censorship, libel and slander, copyright, etc. does not guarantee its implementation. Political will of a government to respect the enabling legal media environment must be repetitively affirmed and concretely applied. Attention should also be paid to laws that are not specific to media activities but still capable of strongly influencing them. The list cannot be exhaustive but includes customs regulations, copyright, taxation, anti-competition laws, etc. Beyond looking at the law on paper, it is necessary to look at the law in practice – i.e. how authorities implement the law. This includes general questions such as, what degree of independence does the judiciary system have? What are the administrative requirements and costs to operate a media? Do authorities actively investigate and prosecute crimes against journalists?

Pay attention to safety

The issue of safety of journalists and freedom of the media is not limited to authoritarian regimes or fragile contexts. Attacks against journalists take place in developed countries and in societies where the media sector disturbs powerful political and economic actors.

Booming use of new ICTs and social media has fuelled the anxiety of governments and powerful private actors who fear losing control over information flows and narratives. As a result, strategic communication efforts to win the ‘battles for hearts and minds’ have intensified. In this battle, persuasion rather than truth is often the most prized quality (Price 2014). Investments in surveillance technologies have also increased, as well as repressive practices aimed to silence activists and critical reporting. UNESCO states that ‘on average, every five days a journalist is killed for bringing information to the public’. Attacks are not limited to war zones. They are often perpetrated in non-conflict situations by organised crime groups, militia, security personnel, and even local police, making local journalists among the most vulnerable. Several indexes, such as the Freedom House and Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) freedom of the press survey, provide essential annual data on the safety of the media in every country (see

Freedom House and

RSF websites).

For possible interventions on safety, refer to the UN Action Plan on the Safety of Journalists (UNESCO 2016)

|

Common cultural values and societal norms have an immense effect on journalists and other media actors. Conversely, media have a deep influence on the evolution of commonly shared sociocultural values. Societal and cultural beliefs influence journalists, owners and other media actors and the selection of news as well as the presentation of events and positions in the media. These may either serve to deepen or to challenge existing stereotypes and prejudices – for example, around gender. Working in conflict and divided environments requires particular attention to societal beliefs and cultural values. Deeply rooted beliefs may ‘naturally’ prevent journalists from reporting impartially, as it can be difficult for them either to be aware of this influence or even to overcome it when needed for balanced reporting. Without critical thinking and awareness of the relativity of one’s own common sense values, media and the journalists are unwillingly using their power to de-legitimise and exclude other ways of thinking. These socio-political and cultural factors also affect how society accepts and perceives the media. Is the media the ‘fourth power’ and a necessary watchdog, or a dangerous and manipulative sector? It depends on the role that society attributes to the media – a role that is fast-changing, not only in fragile contexts but also in ‘emerging’ or ‘old’ democracies.

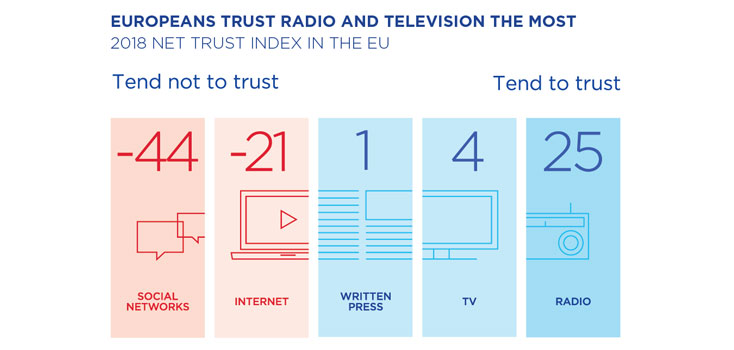

Trust gap between traditional and new media grows [Link]

|

|

Potential interventions

Coordinated and regular assessments with otherdonors and key actors on governance and citizens’empowerment, on citizens’ expectations aboutfreedom of expression and the media. Work with civil society actors to engage as many citizens as possible about their expectations with the media, and support the production of regular opinion polls.Specific training for CSOs on the role of the media and ways to build constructive relationships with media organisations.Working with the media to produce weekly or monthly updates on how information is created, internal processes, the work of a journalist, etc. and fact-checking productions.Encouraging media professionals to critically reflecton their own societal beliefs and stereotyping.Development of curricula for primary or secondary schools, universities and other academic institutions on information and media literacy.

Issues to keep in mind

An analysis of the socio-cultural context and public discourses should help to identify the core grievances and tensions that divide society. Are they discussed in an inclusive, balanced and tolerant manner? If not, what are the marginalised groups that need to have a say and what media platforms could help them to better participate? And how can media platforms be strengthened in ways that will allow inclusive, balanced and constructive dialogue between different constituencies to find common ground and solutions?

To conclude this section, it is important to remember that the media are meant to serve the people. The ’raison d’être’ of the media is to get people reading, listening to or watching content and reacting to it. This means knowing who the media are talking to and offering content that meets audiences’ interest and capacity (taking into account local languages, accessibility, media and information literacy). The audience is thus present and active in all six segments:

With individual journalists – as beneficiaries of media content, audiences are more and more active and participatory, through inputs during call-in programmes, debates, suggestions to newsrooms, or comments on digital platforms.With media outlets – trust-building and loyalty to media are created with media that are close to people’s concerns. The quality of this relationship is assessed through audience surveys measuring listenership, readership, and satisfaction; impact studies measure quantitative and qualitative impact of the media on people. With media institutions – citizens have access to and benefit from accountability mechanisms such as press councils or ombudsmen.With economic and technological factors – citizens value independent media and information as apublic good, and are willing to pay for it (subscriptions, paid-for information, taxes or licence fees). With the political and legal environment, and safety of journalists – citizens make use of their right to access information and to freedom of expression; they participate in the legislative process andsupport measures to protect journalists fighting against impunity.With societal beliefs – the global population benefits from and defends quality media as the ‘fourthestate’. Society defends reliable information that helps people to be engaged and informed citizens.

Yet, in many countries, there are low levels of media literacy and a large digital gap – for example, between people in rural and urban areas, rich and poor households, educated and less educated individuals, and younger and older generations. Media assistance should thus aim to strengthen the capacity of all audiences to play an active and responsible role in information flows. On the one hand, media programmes may remind or make people aware that they have the right to access reliable and independent information; on the other hand, media and information literacy efforts should raise awareness of the responsibilities of media consumers – such as checking sources of information, identifying possible bias in reporting, being aware of one’s own bias, thinking twice before sharing content, calling out misinformation, and valuing quality information and therefore understanding that it has a price. More and more evidence and research calls for information and media literacy programmes as a necessary and complementary component of support for the media sector.

Potential interventions

Promoting an enabling environment for citizen engagement with the media – for instance, participation in radio debates, ‘op eds’ in newspapers, call-ins during talkshows.

Working with media to produce weekly or monthly updates on how information is created, internal processes, the work of a journalist, etc. and fact-checking productions.Working with NGOs and CSOs to conduct awareness campaigns on the role of the media.Developing curricula for primary or secondary schools, universities and other academic institutions.

Issues to keep in mind

Be careful with using and promoting the conceptof ‘citizen journalist’. The contributions of citizens are to be encouraged as providers of raw content to journalists and newsrooms, who then verify, source and assess the importance of the information. Journalism is a profession responding to ethics and professional rules. A citizen does not become a journalist because he/she posts a pictureor writes an opinion piece.Knowledge of the audiences comes from statistical information and studies on media consumption habits. This needs to be cross-checked with data from the media themselves, where such data exists, about audience reach, consumption and feedback. Media and Information literacy programmes must be designed according to assessed needs, by media professionals, and then implemented with partner organisations such as schools, adult training centres, public service agencies, NGOs, etc.

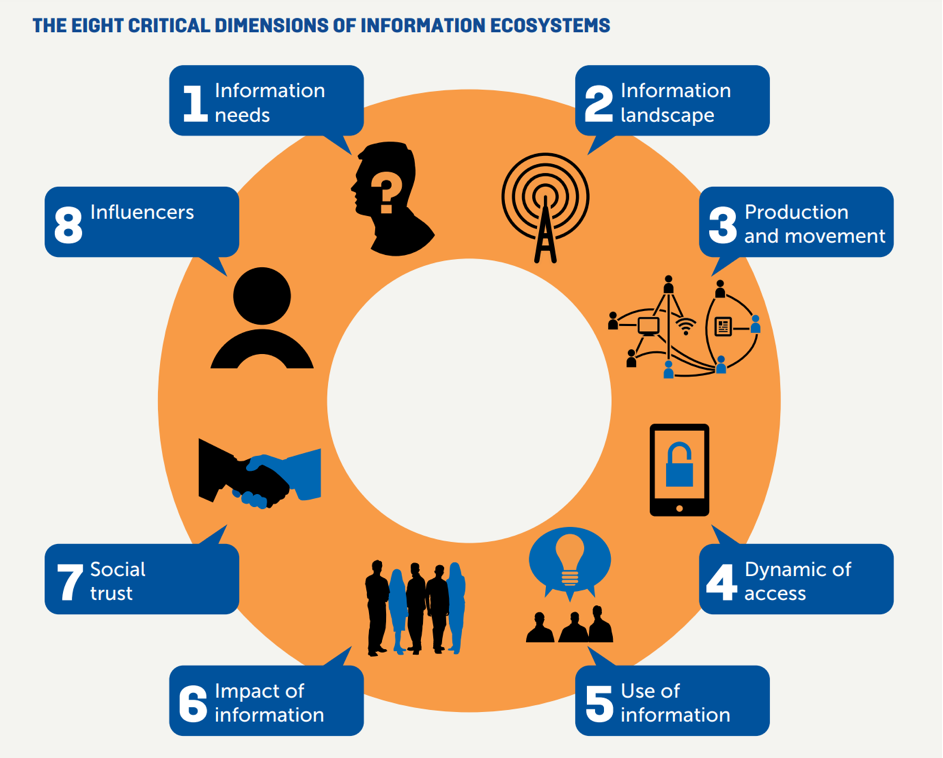

Another conceptual framework developed by Internews includes “Eight Critical Dimensions of Information Ecosystems, which enable a holistic understanding and analysis of the information ecosystem of any given community or place. These dimensions are dynamic and in constant flux, depending on the specificities of each context at a given moment in time.”

|

|

Additional resources

More than 100 resource documents in different languages for journalists Link CFI, ESJ 2020 Alain Rollat, Richard Pernollet, David Servenay, Didier Desormeaux, Brigitte Besse 4 leçons d’un environnement complexe Link Africa Check 2019 Peter Cunliffe-Jones Written by experts in the fight against disinformation, this handbook explores the very nature of journalism with modules on why trust matters; thinking critically about how digital technology and social platforms are conduits of the information disorder; fighting back against disinformation and misinformation through media and information literacy; fact-checking 101; social media verification and combatting online abuse. An International Fund for Public Interest Media - June 2019 Consultation Document Link The Namibia Media Trust NMT 2019 This paper presents a new model for Media Viability at a time when media outlets face enormous difficulties delivering quality reporting while staying financially afloat. Link Deutsche Welle 2019 Laura Schneider The sustainability of the news industry and journalism in South Africa in a time of digital transformation and political uncertainty Link Digital Media Research Centre 2018 Harry Dugmore et al. This briefing focuses on the media of countries that are divided, undergoing crisis or conflict, or where governance is weak. It argues that the role of public service media in such societies – sometimes called fragile states – is increasingly relevant and sometimes critical to underpinning political and social development for the 21st century. Creating a supportive legal environment for the media sector needs more than traditional legal reform. It requires taking into account the local context and the diverse stakeholders and their attitudes to the media. Link Deutsche Welle 2016 Gabor Polyák, Sacha Meuter Terrorism and the fight against terrorism have become major elements of domestic and international politics, with the media firmly on the front lines, especially when attacks target civilian populations. Link UNESDOC 2017 Jean Paul Marthoz Learn more about how nonprofits, movement builders, and other social sector actors can more effectively communicate information to create meaningful change. How press councils have adapted to the digital ages? Have they for instance developed guidelines on the use of algorithms by social media? Do they address issues of online hate speech and disinformation? Are they using ICTs to improve accessibility to media users?

|