The choice of media platforms and formats depends on the targeted populations and their actual access to and use of media in a specific context. We live in an era of multimedia consumption. In addition to the ‘traditional’ media such as TV or radio broadcasters and print media outlets, digital and social media have become ubiquitous thanks to the rise of mobile telephony and internet access, even in less developed contexts. This opens up new opportunities to connect quickly and widely with audiences and to interact with them.

However, journalists increasingly have to produce in multi-media format (words, sounds, images and videos) and to push their content on social media as well as traditional platforms (press, radio, TV) in order to adapt to the rapidly evolving consumption habits of their audiences, particularly younger people. While the use of various formats and media platforms can be complementary and not mutually exclusive, it requires more skills, time, resources and due consideration of the digital divide (see Chapter 2.2, ‘Pressing challenges’).

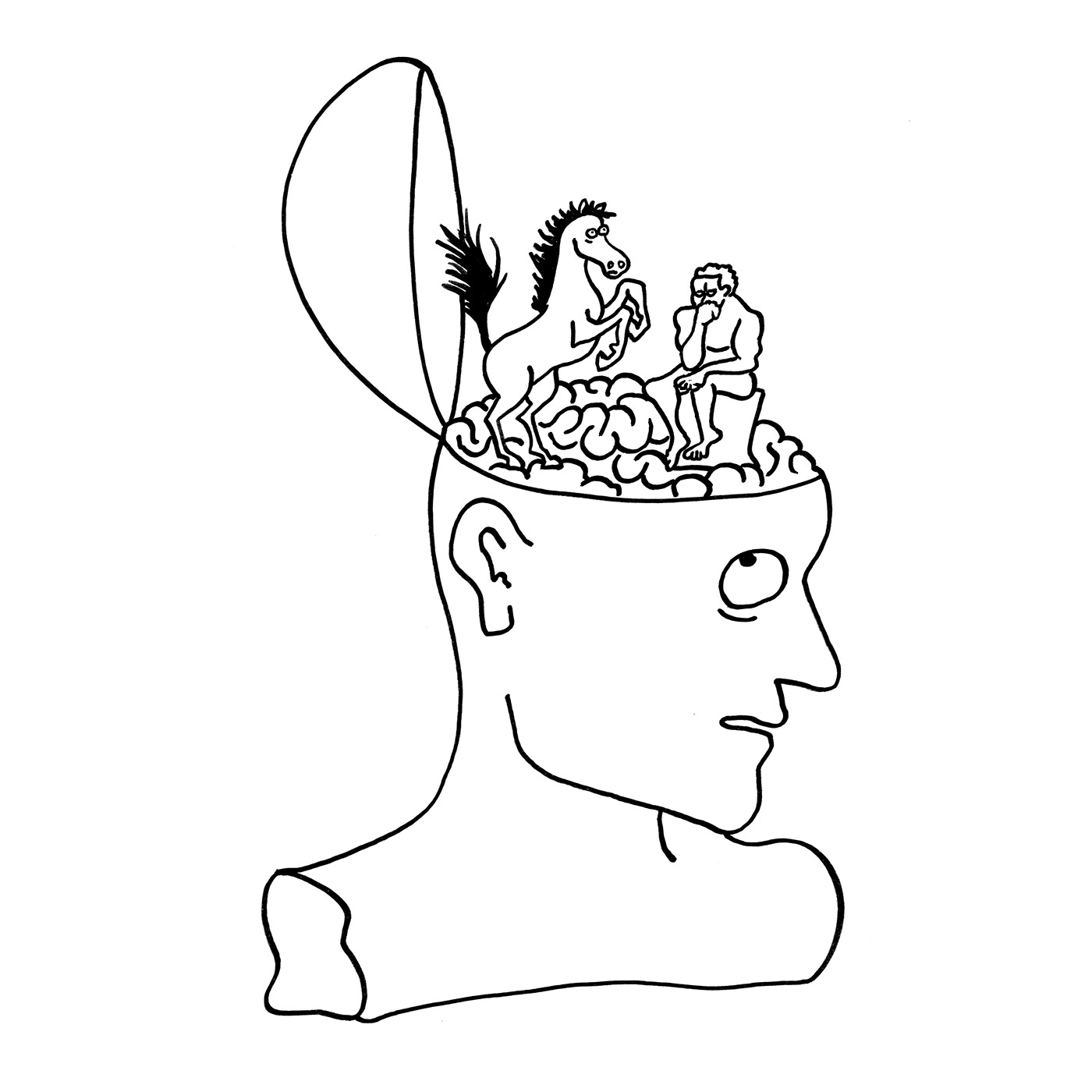

In rural areas, radio often remains the most accessible and sometimes the only mass media available. While considering content, one should distinguish between rational content (such as news and debate programmes) and fictional or dramatic contents (such as soap operas and entertainment) geared towards emotional responses. However, the two are not mutually exclusive and can even complement each other in the broadcast programming of a generalist media. Emotional and rational media content correspond to the two basic systems that govern human behaviour as social and personality psychology has demonstrated: so-called ‘system 1 thinking’, which is fast, instinctive and emotional, reflecting the reptilian brain, which runs on emotion and instinct; and ‘system 2 thinking’, which is slow, deliberative and more logical (Kahneman 2011).

Much media content, particularly on the internet and social media, feeds system 1 thinking, and the need for immediate, emotional content. However, democracies largely aspire to run on system 2 logic, with the institutions and principles that underpin them resting on the assumption of rational citizen, factdriven decisions and a deliberative public sphere (Bartlett 2018). The thinker and the horse: inspired by Daniel Kahneman and his book

Thinking Fast and Slow. His central thesis is a dichotomy between two modes of thought: "System 1" is fast, instinctive and emotional; "System 2" is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. |

|

Another distinction is between partisan versus non-partisan media content. Media content that strives for impartiality should clearly distinguish between facts and opinions and should seek to balance different points of view. The goal is to enable the media consumer to make up his or her own mind. The goal of impartial media content is to inform; partisan media content seeks to convince.

Again, a variety of media productions allow for a combination of the two types. For example, the same media can broadcast factbased news and balanced debates on the one hand, and on the other, more partisan programmes designed to convince audiences to adopt certain behaviours. However, there should be a clear distinction between these two different types of programme in the media productions. Blurring the distinction between the two endeavours can be self-defeating as it might create false expectations on the providing side and genuine apprehension or distrust on the receiving side.

A non-partisan and public service-oriented media allowing for the different viewpoints to meet and for dialogue on a balanced and fair basis remains a key component of a healthy media landscape, particularly in fragile and divided societies.

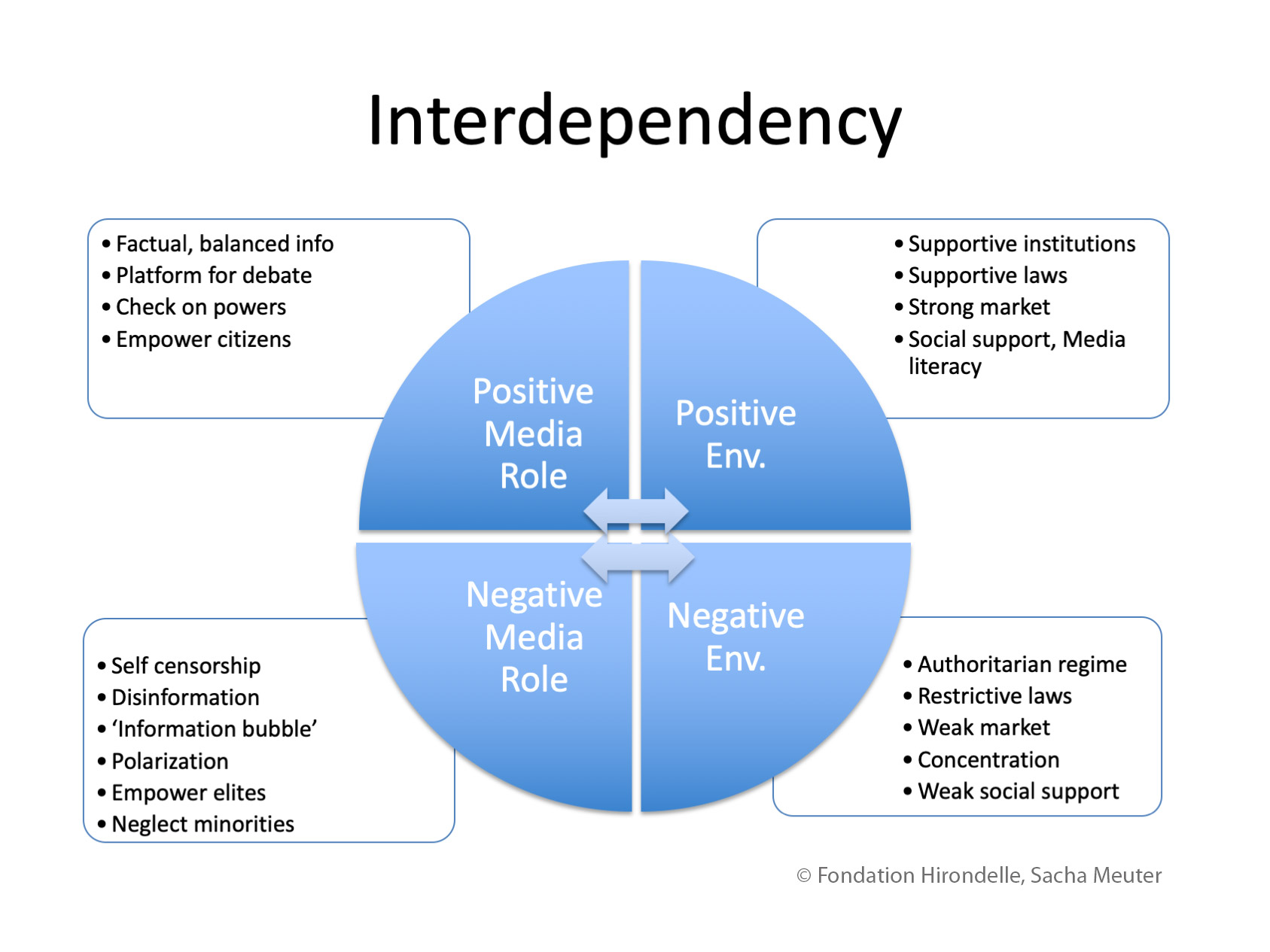

The media and the environment they operate in can mutually reinforce each other in a positive or a negative way:

Independent and responsible media can contribute to but are also conditioned by the existence of an enabling environment characterised by institutions such as supportive laws and regulations, support from political actors for free press, healthy markets, active citizens, supporting educational bodies, and professional associations.

A negative environment – characterised by an authoritarian state, a flawed legal and regulatory framework, political actors that see the media as either mouthpieces or adversaries, passive citizens, weak markets, or a lack of supportive civil society and educational institutions – leads to and is reinforced by a flawed or captured media system that produces biased information, analysis and propaganda, polarises public views, and suppresses cultural diversity and shared identities.

Relationship of Interdependency: the media sector is a reflection of its wider environment, in the sense that a positive environment (i.e supportive laws, market, institutions, media litteracy) enables the media to play a positive role in the society.

In return, there are evidence that media fulfilling their social functions contribute to promote a more democratic environment.

|

|

Hence, the media cannot be considered in isolation from their environment. The media can contribute to the promotion of a more democratic society (e.g. fighting corruption, encouraging participation in political processes, etc.) but cannot do so alone. Improving the media’s capacity to play a constructive role requires a strategy to analyse and foster the conditions for a broader enabling environment.

Additional resources

Younger audiences are different from older groups not just in what they do, but in their core attitudes in terms of what they want from the news. Young people are primarily driven by progress and enjoyment in their lives, and this translates into what they look for in news. Link Flamingo 2019 Nic Newman The Media Development Indicators define a framework within which the media can best contribute to, and benefit from, good governance and democratic development. Media Freedom Navigator provides an overview of different media freedom indices. Navigate the map in order to access media freedom data for each country and background information on each index. For reading material, examine the resources section. * Media freedom has been deteriorating around the world over the past decade. * In some of the most influential democracies in the world, populist leaders have overseen concerted attempts to throttle the independence of the media sector. * While the threats to global media freedom are real and concerning in their own right, their impact on the state of democracy is what makes them truly dangerous. * Experience has shown, however, that press freedom can rebound from even lengthy stints of repression when given the opportunity. The basic desire for democratic liberties, including access to honest and fact-based journalism, can never be extinguished. Link Freedom House 2019 Sarah Repucci Link Reporters Without Borders 2019 Advances in behavioural, decision and social sciences show that humans are not purely rational beings. As a result, this report brings new insights to political behaviour. It calls upon evidence-informed policymaking not to be taken for granted. Link European Commission 2019

|