The media are key intermediaries between individuals and the rest of the society. The media also play an important role in shaping the very nature of society. They connect citizens with what is happening around them and with the prevailing social, economic, cultural and political institutions. The media also provide channels for these institutions to interact with citizens.

In the digital era, the term ‘media’ is sometimes used to encompass, without distinction, all the popular information and communication technologies (ICTs) (e.g. mobile phone and social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube). However, for the purpose of this guidance, the term ‘media’ is not to be confounded with simple communication channels. We use the term to encompass both online media and traditional mass media houses such as press, radio and TV stations, but more specifically those media that are expected to be bound by journalistic ethics, and other professional standards, with specific roles to fulfil.

The first role conferred on media and journalists is to report on what is going on in the world and to provide impartial, fact-based information of public interest. By doing so, the media can help citizens to take informed decisions and to govern themselves.

In 2015, Mungiu-Pippidi published the results of a major analysis of the data available on corruption. The role of a free media had among the greatest effects in limiting corruption (alongside other actors, such as civil society). Mungiu-Pippidi concluded:

“We found evidence that a society can constrain those who have better opportunities to spoil public resources if free media, civil society and critical citizens are strong enough.”Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015)

The Quest for Good Governance: How Societies Develop Control of Corruption. Cambridge University Press, p.56

|

|

However, media and journalists do not only mirror reality, they also construct it. The media can either balance or amplify a ‘natural asymmetry of information’ between those who govern and those who are governed, and between marginalised groups and the rest of the society (

Islam 2002). By contributing to a more inclusive and deliberative public sphere, the media can help in the identification of shared interests and shared identities within society, and in the building of consensual solutions to conflicts.

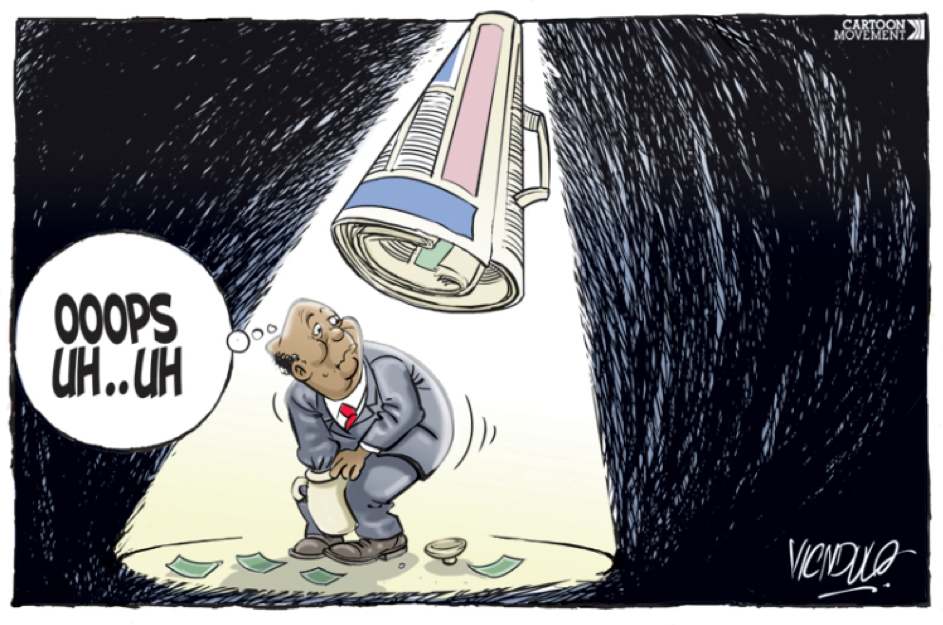

The media can also act as a watchdog, speaking on behalf of citizens, disclosing abuses of power, challenging political authority, and holding powerful people to account.

Thus, as intermediaries, the media perform a variety of roles:

• disseminating information on relevant topics

• giving voice to different parts of society, including marginalised groups

• providing a forum for exchange of diverse views and dialogue

• providing channels for political actors to raise the public’s attention, and to communicate and interact with citizens

• fulfilling a watchdog function vis-à-vis those in power

• influencing the perception of social norms and realities

• contributing to social integration.

Considering these multiple roles in state and society, it is evident that a healthy media sector is an important factor in promoting inclusive and effective development. It contributes to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Agenda 2030, particularly SDG 16, by fostering inclusive, just and peaceful societies.

However, the media often fall short of their responsibilities as providers of public interest information, platforms of inclusive dialogue, and watchdogs speaking truth to power. Instead, the media often act as mouthpieces of the powerful, repeating rumours without verification, discriminating against minorities and feeding the polarisation of societies. Today, in many contexts, the media sector faces significant challenges, as discussed below.

The media are increasingly confronted by measures aimed at silencing critical voices and providing oversight. Restrictive laws, punitive legal measures, barriers to advertisement revenues and physical violence combine to restrict media freedom. These factors violate several human rights, including the right to freedom of opinion and expression, the right to information and the right to life. Too often, these threats emanate from governments, and even when they are not the source of the problem, governments often fail to provide solutions to counteract the actions of those who attack media freedom.

In the early 2000s and in the wake of the Arab Spring, the Zeitgeist was largely techno-optimist and focused on the empowering potential of ICTs. Yet in a relatively short space of time, attention is increasingly being drawn to how ICTs are contributing to this shrinking of public space.

All over the world, ICTs can provide alternative spaces for civil society to organise and collaborate. However, they also provide authoritative states and private actors with unprecedented surveillance and censorship capacities. It is therefore paramount to assess the risks attached to the use of ICTs and to choose the right technologies according to the local context. This might include training partner organisations in cybersecurity and, when deemed necessary, moving away from online spaces to engage in offline bridge-building initiatives (see, for example, Widmer and Grossenbacher 2019).

It is also important to consider who has access to different types of ICTs. While access to internet and mobile phones is growing, in many developing contexts there is still a large gap between those who have access to those technologies and know how to use them, and those who don’t. The digital divide therefore risks deepening already existing inequalities – for example, between rural and urban areas, between rich and poor families, between educated and uneducated people, between younger and older generations, and between men and women. (In least developed countries (LDCs), women use the internet 31 per cent less than men on average) (Sambuli 2018). Efforts must therefore be people-oriented and not technology-driven. More fragmented and polarised public sphere

Digital and mobile technologies present people with overwhelming information options. In this flood of information, the algorithms of social media and web search engines are designed to put before us the online contents we are most likely to click on. These two factors combined reinforce our natural tendency to consume information that confirms our pre-existing biases. As a result, we are increasingly trapped into echo chambers of like-minded tribes. Our capacity to find common ground with antagonist groups therefore diminishes, and so does the trust of citizens in their institutions. Ultimately, this undermines deliberative democratic processes, atom is ing the public sphere into special interest constituen cies that lack the capacity to talk to and respect each other.

Misinformation and disinformation are one source of social tension and conflict, but a broader issue is the increasing fragmentation and fracturing of media and the decline in independent media capable of engaging people across societal fracture lines. The capacity for societies to negotiate difference has also been undermined as channels for public debate, shared public spaces and trusted reference points for national public conversation have often declined markedly in recent years. Suspicion and often blaming or stigmatising of the “other” in society has grown.

James Deane,

Fragile States: the role of information and communication, BBC Media Action Policy Briefing 2013

|

Disrupted business models

The digitalisation of communication flows creates situations of monopolistic control and capture of advertisement and subscription revenues by actors such as the GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft). It jeopardises the business models and the sustainability of news media. A frequent strategy in this context is to cut costs as much as possible, pressuring journalists to deliver a maximum of articles in a very short space of time. This means journalists have less and less time to search for and cross-check information. They increasingly rely on reports from press agencies, making the media content more homogenous, and less attractive to the public. This in turn weakens the media’s anchoring in society.

Misinformation and disinformation (1)

Less viable media houses are more easily captured by partisan political or financial interest groups. Furthermore, social media and web search enginescreate the dangerous illusion of access to free and unmediated information flows – at a time when fake social media accounts and algorithms are increasingly being used by those who want to target the grievances and vulnerabilities of audiences to confuse or manipulate them as amplifiers.

As a consequence, trust in traditional media and journalists as information gatekeepers is being eroded. The role of journalists tends to be disregarded, at a time when the need for professionals who are trained and paid to check information and prioritise it according to public interest is greater than ever before.

It is essential to strengthen the capacity of the media to overcome these substantial challenges. SDC therefore remains committed to trying to contribute to a healthy public interest media sector.

(1) See glossary (

Annexe 2) for definitions of disinformation, misinformation and mal-information