Adaptive management: What is it?

Adaptive management (AM) comprises of a set of approaches that respond to the fact that development programmes are designed and implemented in contexts that are complex, dynamic and unpredictable. Because of these features, it becomes impossible to chart out the trajectory of interventions through a preset theory of change: from the programme inputs, to intermediate outputs, to the final (desired) outcomes. Instead, reaching the desired outcomes requires a combination of best guesses in a theory of change, learning by doing, and subsequent adjustments based on revisions to the theory of change and related activities.

It is important

to distinguish between pro-active and re-active adaptive management:

Re-active AM relies on regular monitoring and reflection activities to detect unpredicted challenges and, when needed, to adjust planned actions to remain on track to achieve the desired programme outcomes.

Adaptive management can be defined as a systematic process for continually improving management and implementation of development programmes by learning from previous or ongoing implementation. Adaptive management obviously requires institutionalisation of a process that can continuously monitor implementation, regularly harness lessons through reflective practice and adapt activities and management in response, and change overall programmes as required.

|

Within the SDC this is common practice, and the SDC is also seen as a donor that is very “flexible“.

Pro-active AM scans the horizon for opportunities and risks, and it adapts to take advantage of them. It explicitly plans for experimentation and regular upgrading of the strategies; it considers learning and the reduction of uncertainty and imperfect knowledge as one of the key objectives of the management effort.

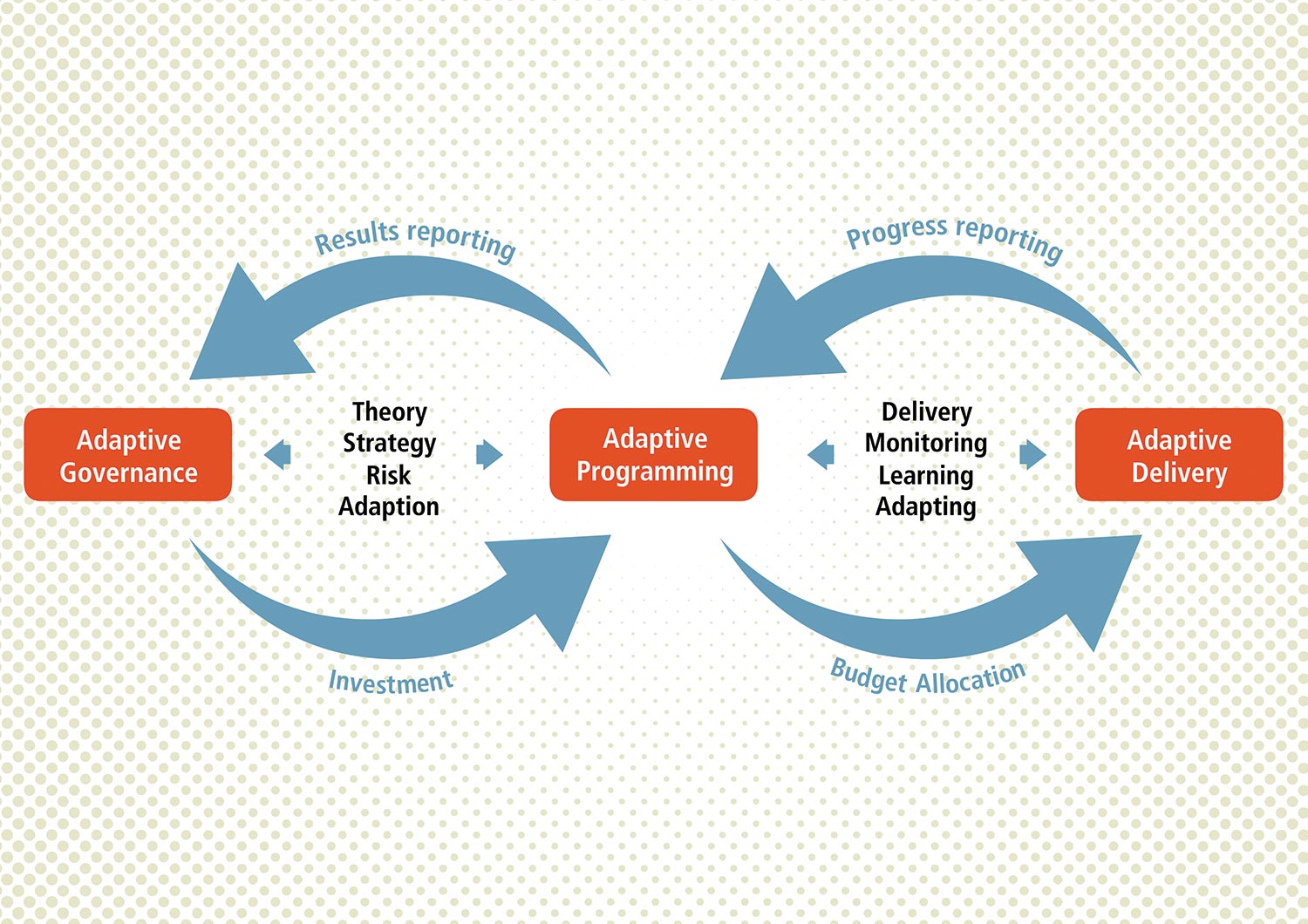

Different levels of adaptive management within SDC

Adaptive Governance is the realm of SDC’s headquarters in Bern, approving progammes and establishing the rules for contracting. Headquarters needs to have an understanding of the evolving context and focus on setting programmes’ high-level objectives (including reassessing them with changes in context), and approve the levels of risk that are tolerable as well as the strategy for adaptation.

Adaptive Programming is within the remit of the SDC’s country offices. It involves understanding the concrete steps of the adaptation strategy, includes whether programmes are on track within the theory of change to meet objectives, and if not, what can be done in terms of reallocating resources or reassessing goals in the changed context.

Adaptive Delivery is the responsibility of implementing partners. It involves thinking about how particular progamme outcomes might be achieved, by hiring or making contact with politically savvy local staff, establish loops of adaptation and learning with all involved, and if the current set of activities are not delivering, decide on which timely changes are needed to improve the situation.

Each of these components points to responsibilities at different levels of interventions, from the most local delivery processes, to the highest donor decisions about broad governance strategies.

Figure 1: Different levels of adaptive management, adapted from Green and Christie (2019)

Integrating into programming Integrating adaptive management into development progammes requires specific organisational culture, processes and tools.

Culture. Adaptive organisations require an organisational culture and staff who are comfortable working with uncertainty, able to be flexible and willing to take well-judged risks. This organisational culture needs to permeate from the headquarters to the cooperation offices and should include the staff of implementing partners. Staff, especially implementation partners and cooperation office staff, need to develop broad networks across a range of stakeholders for gauging the pulse of a particular change. Moreover, staff at all levels need to be trusted by superiors and be provided with discretionary powers so that they can respond to changing situations in time. Staff should be encouraged and supported in reflecting and analysing context dynamics and reflecting on the challenges for interventions – and not sticking to preset plans for delivering results at any price. This culture is not always easy for an organisation that is used to establishing and following standard processes and aims at doing things the same way.

Processes. It is important to note that adaptive management is not a retroactive justification for an “anything goes“ approach. In order to build an organisation that has continuous learning hardwired into its DNA, comprehensive documentation that makes decisions transparent and accountable is necessary. Creating and maintaining this institutionalised memory not only guards against the loss of previous learnings as staff change, but it also enables managers to justify decisions with backup documentation and reasoning. For adaptive organisations, well-resourced documentation of monitoring, lessons learned, decisions made, and adaptation attempted is at the heart of the approach.

Tools. Apart from an (ongoing) context analysis (MERV, Political Economy Analysis, power analysis, conflict sensitivity analysis, stakeholder analysis, risk assessments), a variety of tools and methods have been suggested that are a natural fit for adaptive management – some of which are already used by the SDC.

Adaptation: Strategy testing, scenario forecasting, “fail fast and forward”, risk mitigation matrix.

Figure 2: Relevant questions asked in different processes used for adaptive management